Firesafe has just been developed and uploaded to github

Firesafe is a technology to enforce data integrity, and enable complex transactions, on Firebase.

Firesafe compiles hierarchical state machines (HSM) definitions into Firebase security rules. The Firesafe HSM language is expressive, and a super set of the Firebase security language. Adding consistent, concurrent and fail safe protocols to Firebase is now a whole lot simpler (e.g. cross-tree transactions).

Firebase is already the future of databases, offering scalable low latency database-as-a-servie. Firesafe, compliments this amazing technology with an expressive syntax to get the most out of its security model. (Firesafe is not endorsed by Firebase)

Motivation

In multiplayer apps/games, people cheat. It’s a loss of direct sales, AND the free loaders also diminish the fun for everyone else. Multiplayer games are webscale, which means the old solutions to data integrity and transactions don’t work (e.g. SQL).

Firebase solved one problem of the cost of providing low latency persistent data storage to mobile and desktop games. It’s the first scalable NoSQL hosted solution that didn’t suck. It also provided an unorthodox security and transactions abstraction. Turns out that abstraction has enough purchase to do some really cool things not possible in many NoSQL environments. Unfortunately, properly configuring the security layer is extremely verbose and error prone. Firesafe makes it easy.

Proper data integrity is very important, especially when users have something to gain. A classic game exploit is the "item clone". In this exploit, a player gives an item to a friend, and yanks their connection to the game. Now, the player and the friend have the item. Various variations exist, some not even requiring a friend.

- Zynga: http://gamersunite.coolchaser.com/topics/31432-farmville-how-to-duplicate-items-no-scam-or-hack

- Kixeye: http://bpoutpost.com/battle-pirates-glitches-cheats-ghosting-cloning-fleets.html

- World of Warcraft: http://eu.battle.net/wow/en/forum/topic/3313135576

The reason why many games are effected by the same type of bug is that a difficult technical issue lies behind the exploit. It is very had to enforce the semantics of a cross user transaction.

Firebase can solve this with a two phase commit protocol. Classic literature on 2 phase commits state it can become deadlocked. However, normal deadlock issues don’t arise in this case, because Firebase is a central authority, and clients state’s are persisted on disconnect. Unfortunately, actually writing a two phase commit protocol in Firebase security rules is actually really hard and error prone, and the 2-phase commit protocol was one motivation for creating the Firesafe abstraction of Hierarchical State Machines (HSM) in Firebase.

However, while HSM will prevent silly mistakes, it still can’t prevent high level protocol errors. We are currently connecting Firesafe to a theorem proover. One this is complete will we be able to prove non-blocking properties and protocol invariants for arbitrary HSMs. Our long term goal is to make "provably secure, deadlock free, multi-user interactions" simple.

The HSM Language

In Firesafe we provide the Hierarchical State Machines (HSM) language. A similar language (UML statecharts) is often used in protocol design. A machine is a set of states and a set of transitions between them. Each machine gets compiled down to a single, massive ".write" rule.

The language has a very natural graphical representation. To explain the language lets start with simple examples and build up to a two phase commit protocol for secure exchange of items between players.

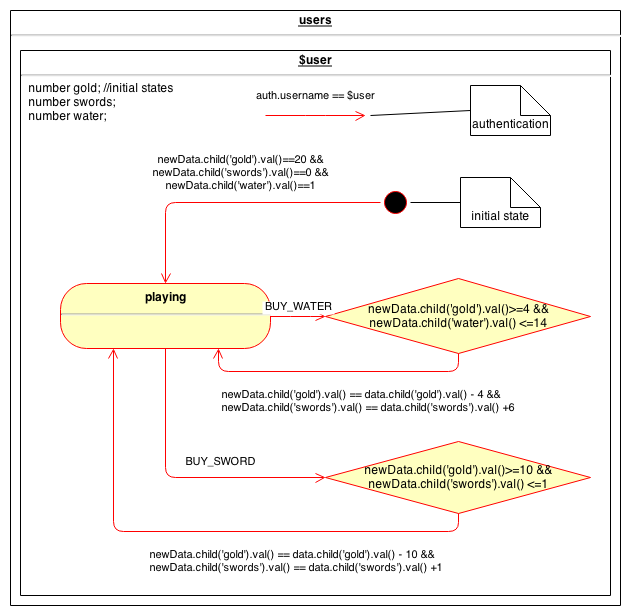

Example: Shop

One common source of complaints and support headaches is buying items in-game. If it goes wrong players could lose currency, or, if it’s exploitable, cheaters profit and devalue the currency. This is an acute problem if the currency is bought with real world money.

In a normal Firebase setting user accounts are represented as wild card ($user) children of "users". By placing our state machine as a child of "$user", Firesafe will generate an state (and signal) variable as a child of any "$user" nodes.

We create secure Firesafe variables: gold, swords and water, at the same hierarchical level as the state machine. This indicates those variables values are protected by Firesafe. They can only ever be tampered with by a connected client if explicitly mentioned in a "guard" of "effect" clause of the machine.

In the shopping scenario a user has just a single state, "playing". New players won’t have Firebase data initially, so the black circle represents the initialization. New clients cannot initialize their new user accounts to anything though (a source cheating). Effect clauses denote post conditions of Firesafe variables, which must evaluate to true. Any Firesafe variable not mentioned in an effect is locked. Guard and effect clauses are expressed as normal Firebase security expressions. In the shop case, the diagram forces clients to initialise their accounts with:

{

state:"playing",

gold:100,

swords:0,

water:0

}Once a player is playing, they have two options in the shop, buying a sword or water. Both these transition are labelled, which indicated the client must state which signal they are using. In this example we use a guard to ensure the player has enough gold to make a purchase and they do not exceed a maximum for the items (max(swords) 2, max(water) 20).

Guard clauses (diamond) prevent transitions unless the guard evaluates to true. The guard in the shop ensure the player has the money and space in their inventory. So to buy a sword after initialization when the user has 100 gold and 0 swords, the new player can update { signal:"BUY_SWORD", gold:90, swords:1 } on their "/user/

The final diagrammatic feature worth mentioning is the unattached red arrow. Unattached arrows on a digram denote a transition type. Transitions only occur if their type clause evaluates to true, which commonly used to express permissions. In the shop we only allow the owner of the user record to invoke transitions. The transition type in particular is an excellent building block for complex multi-user interactions, because you can easily express some transitions can only be performed by certain user roles.

- complete hsm source file – https://github.com/tomlarkworthy/firesafe/blob/master/models/shop.hsm

- generated validation rules – https://github.com/tomlarkworthy/firesafe/blob/master/models/shop.rules

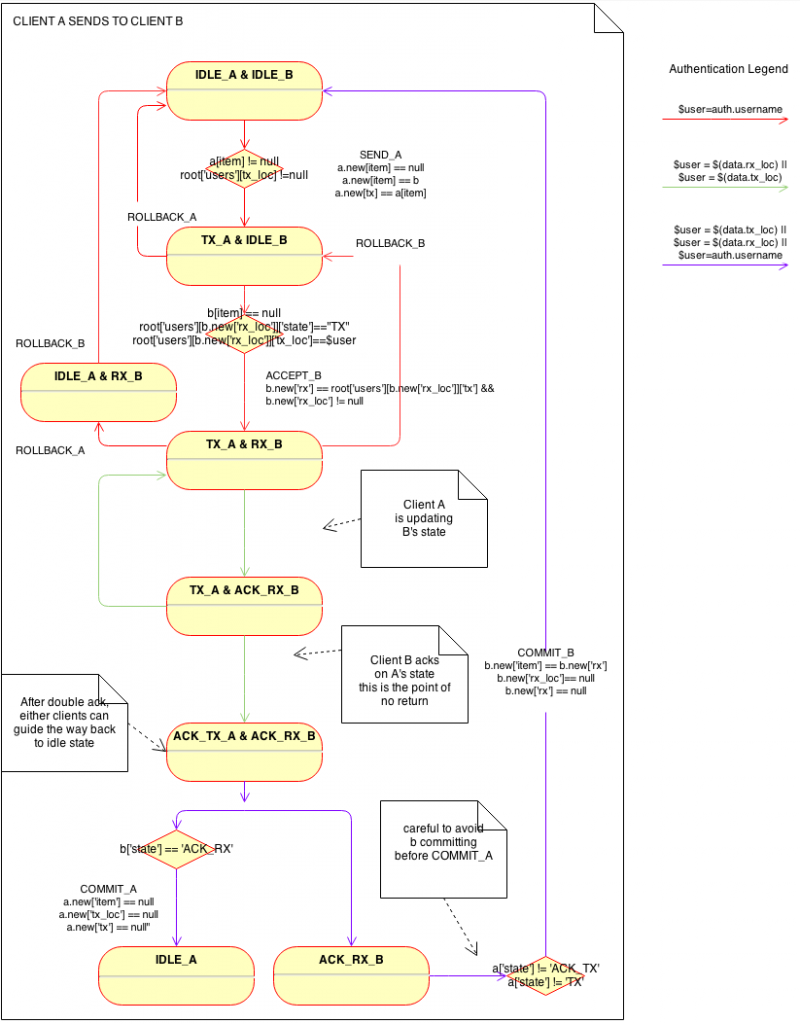

Example: Item Trade

Sending items from one player to another is problematic in many games and applications. Firebase natively does not offer much help, as Firebase transactions occur only on a subtree. To exchange items across users, you need to transfer data between different data trees (a cross-tree transaction). Firebase’s atomic transactions cannot express this case, so the trade must be broken down into several smaller transactions Firebase does support.

One background issue is that a user might disconnect at any time (possible deliberately). One player disconnecting should not trap the other player in an unescapable state (a.k.a. deadlock).

A cross tree transaction should either 1. occur, or 2. error and rollback. For a trade, an important invariant is the total number of objects in the world do not change. Drawing inspiration from existing literature, we adapt a 2-phase commit protocol using in the banking sector for distributed balance trades, to implement trade on Firebase.

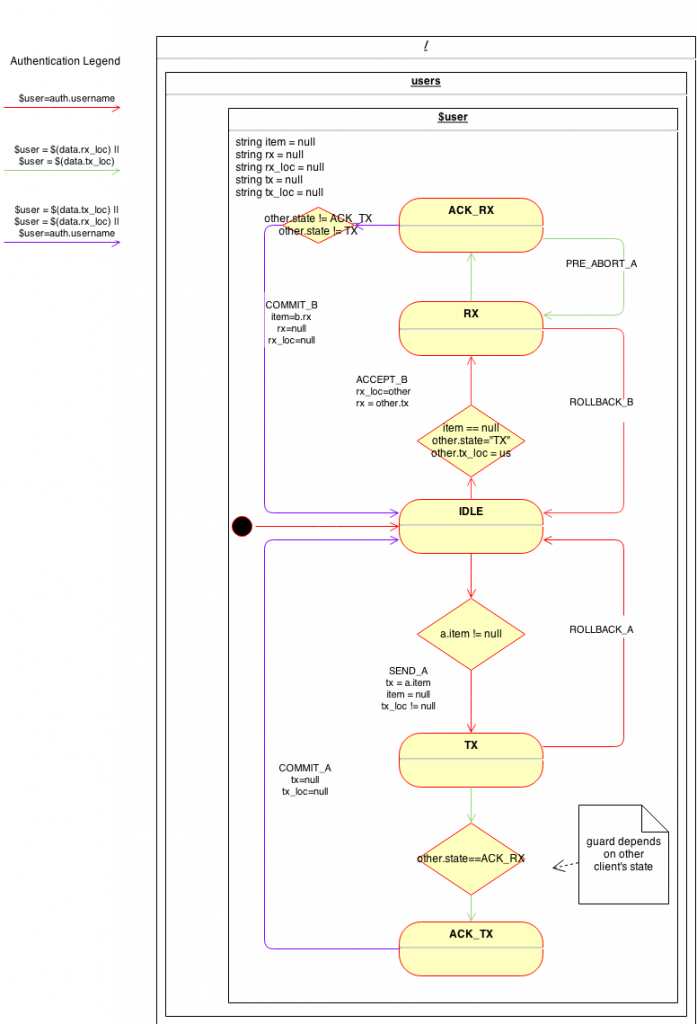

Each user is either, IDLE, sending an item (TX) or receiving an item (RX). Furthermore, the one partner in the trade must acknowledge the others actions in a 2-phase commit, so some additional acknowledgement states are required (ACK_RX, ACK_TX).

Although both trading partners are both users, and thus running exactly the same state machine protocol, it is very difficult to visualise all the interactions without explicitly treating the receiver and sender as different state machines. Thus our first diagram is an aid to visualization. Each state is the product of both parties state. So an individual state of the joint diagram is the state of the sender (user A) & receiver (user B).

(guard and effect clauses have been lossy compressed for readability, see below for actual clauses)

Our protocol is split into several stages. First, the sender indicates he wants to send a specific item to a specific player, by transitioning to the TX state. They must move the item out of the item slot and into their tx slot used internally for the protocol (for illustration we are sending "GOLD"). They indicate who they are sending to by writing the target username into the tx_loc slot, which acts like a pointer to stop disinterested parties being involved.

{

state: "TX",

item:null,

tx:"GOLD",

tx_loc:"receiver"

}Firesafe generates rules that will disallow the transition if the player has nothing to send, or if the target player does not exist, through the guard rules:

data.child('item') != null &&

root.child('users').child(newData.child('tx_loc').val()) != null",Furthermore, the effect is that the value in item is transferred into tx by the effect clause

newData.child('tx').val() == data.child('item').val() &&

newData.child('tx_loc').val() != null"Once a sender is trying to send to somebody, a receiver can transition into the RX state with:

{

state:"RX",

rx:"GOLD",

rx_loc:"sender"

}This time, the guard checks that the receiver has room to receive the item, and that the sender is in the right state, and that the sender’s tx_loc is pointing to the receiver. Note, we use Firebase’s root var and the rx_loc pointer to navigate to the other users record to test conditions.

data.child('item') == null &&

root.child('users').child(newData.child('rx_loc').val()).child('state').val() == "TX" &&

root.child('users').child(newData.child('rx_loc').val()).child('tx_loc').val() == $user",The effect is that the rx_loc must match the sender, and the rx slot must match the item being transferred.

newData.child('rx').val() == root.child('users').child(newData.child('rx_loc').val()).child('tx').val() &&

newData.child('rx_loc').val() != null"Once the receiver is ready, the sender must acknowledge the status change of the receiver. Unlike previous transitions, The sender changes the state state of the receiver. To indicate the different roles within a state machine, we use different transition_types:

".transition_types":{

"self":"$user == auth.username",

"other":"auth.username == data.child('rx_loc').val() ||

auth.username == data.child('tx_loc').val()",

"either":"$user == auth.username ||

auth.username == data.child('rx_loc').val() ||

auth.username == data.child('tx_loc').val()"

}We have self, other and either transition types to indicate the transition can be carried out by the owner user record, the other party in the trade, or either party. Thus, the transition rule for sender acknowledgement on the receivers state machine is:

"ACK_RX":

{

"from":"RX",

"to":"ACK_RX",

"type":"other"

}"The receiver does an ACK_TX similarly on the senders machine. Once both sender and receiver have ACKed. The transaction passes the point of no return.

Because either party could disconnect from Firebase at this point, we allow either party to commit the final stages of the transaction. This is indicated by setting the type to "either".

The sender finalizes by setting the item, and other variables, to null, double checking the other party is in the ACK_RX state (remember they are transitioning from ACK_TX too). Thus the sender can only commit once both parties have ACKed.

"COMMIT_TX":{"from":"ACK_TX", "to":"IDLE", type:"either",

"guard":"

root.child('users').child(data.child('tx_loc').val()).child('state').val() == 'ACK_RX'",

"effect":"

newData.child('item').val() == null &&

newData.child('tx_loc').val() == null &&

newData.child('tx').val() == null"

}For the receiver to finalize, the receiver transitions back to the IDLE state, but copies the data in the rx slot into their item slot, thus gaining the item. Care has to be taken the COMMIT_RX is only possible after the COMMIT_TX is performed (see the guard). We do not want the COMMIT_RX to occur after the first ACK_RX but before the ACK_TX.

"COMMIT_RX":{"from":"ACK_RX", "to":"IDLE", type:"either",

"guard":"

root.child('users').child(data.child('rx_loc').val()).child('state').val() != 'TX' &&

root.child('users').child(data.child('rx_loc').val()).child('state').val() != 'ACK_TX'",

"effect":"

newData.child('item').val() == data.child('rx').val() &&

newData.child('rx_loc').val() == null &&

newData.child('rx').val() == null"

}Additional rollback transitions are required so that either party can back out if one goes offline before the double ACK_RX + ACK_TX. Item states can be restored using the information in the tx and rx variables of the sender/receiver, but it adds little to discuss those transitions here.

While it is natural to develop the protocol using two distinct state machines, in reality the user state machine is identical for both parties. In the following diagram we re-roll the joint diagram into a single HSM ready for code generation. (todo: update diagram with latest notation)

We do not make any promises about the correctness of this protocol … yet. In particular, we are not sure whether a deadlock can exist when the sender quickly moves onto a different trade with a another user. However, verifying the protocols is a high priority for Firesafe, so sign up to our announcements if this is important to you https://groups.google.com/forum/?hl=en-GB#!forum/firesafe-announce

- complete hsm source file – https://github.com/tomlarkworthy/firesafe/blob/master/models/send_item.hsm

- generated validation rules – https://github.com/tomlarkworthy/firesafe/blob/master/models/send_item.rules

Example: Hierarchical State Machines

So far the machines discussed are flat. If you have ever tried to use a finite state machine in a real world setting you might have found yourself replicating arrows until your diagram is an unmanageable mess. Finite state machines suffer from state space explosion. Nesting states addresses this issue by reuses transitions via an inheritance-like mechanism.

Miro Samek in the book "Practical UML Statecharts for C/C++" explains how to use state nesting, and explains common "patterns" for scalable state machine application. Slide 18 onwards of this online presentation explains why HSMs are so much better than FSMs in brief http://www.slideshare.net/quantum-leaps/qp-qm-overviewnotes

Note our HSM do not map directly onto UML statecharts. In particular, UML statecharts are deterministic, whereas Firesafe’ are not. In our HSM implementation, you do not need to specify signals at all, and can therefore leave the behaviour of the state chart ambiguous. While the behaviour of firesafe is ambiguous server side, the client still has to explicitly decide which states to move into. The client logic is often not modelable by state machines. Hence, non-deterministic hierarchical state machines are a better formalism for modelling server side data integrity that the deterministic formalism. That said, much of Miro’s material is applicable to Firesafe’s formalism, and the "Practical UML Statecharts for C/C++" book a thoroughly recommended resource (Note: we are not in any way endorsed by either Miro Samek or Quantum Leaps, LLC, we just love their software!).

Firesafe Status

current

- .hsm -> Firebase rules command line compiler complete

under development

- Transitions with TIMESTAMP examples

- Formal protocol verification

- Draw.io -> .hsm converter

on roadmap

- .hsm -> client state machine generator

- HSM Generics??

Updates for major developments or calls for help! firesafe-announce

Requesting features, or just chat, at firesafe-dev

Using Firesafe

Install with NPM

npm install -g firesafeRun

firesafe <src_hsm> <dst_security_rules>upload the generated file to your Firebase security rules via the web API. We can automate this if it is a highly requested feature (we have a test driven framework).